Section

5

Assessing Adiposity

Various measurement methods may be used to assess body composition, and specifically adiposity, when conducting research and evaluation in clinical and field-based settings, such as early care and education venues, schools, and community-based, childhood healthy weight programs.

They include anthropometry and in-vivo (within a living organism) body composition techniques. These methods vary in reliability, validity, participant acceptability, cost, and technical complexity. Each method has advantages and disadvantages (summarized in Table 1) and some degree of error that relates to the underlying assumptions in the estimate of body fat as well as errors due to the actual measurements (measurement error). Certain methods cannot be used in children with specific health conditions or disabilities because basic assumptions of the method may be violated, or children may have physical or functional limitations that prevent use of these methods.

The choice of a body composition measurement method depends on the goal of the study or evaluation, the type of tissue to be assessed, the study population, and the setting and resources available. Specific factors to consider when selecting a method include:

- validity in estimating body fat

- reliability

- sensitivity to change over time or with interventions

- ability to predict health risks or outcomes (i.e., clinical validity)

- availability of reference ranges or norms for the study population (i.e., having data from a standard or reference population for comparisons)

- accessibility of the tools and/or equipment and staff in terms of training and level of skill needed

- cost

- degree of burden and/or risk and acceptability to the participant

Validity refers to truthfulness of a value obtained or the closeness of a measured value to a gold standard or known value. In obesity-related investigations, the gold standard of direct measurement of body fat and other tissues is difficult to obtain; therefore, the validity of a method for assessing body composition is evaluated by comparison to another method that is considered more accurate but is not the gold standard. In clinical research of body composition, the 4-compartment model is considered the criterion or reference method.49 In this model, four components are measured: total body water (TBW) by deuterium dilution technique, body volume by air displacement plethysmography from which body density (Db) is derived, total body bone mineral (M) by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), and body mass (i.e., body weight) using a scale. Combining the output from these four measurements in an equation allows for estimation of FFM and FM or percentage body fat. Because TBW and bone mineral are found within the FFM compartment, an advantage of the 4-compartment model is that it accounts for variations in the composition of FFM due to differences in bone mass and hydration, which are the two components whose variations have the greatest effects on the accuracy of fat estimations. This is important, for example, in maturing children, where hydration of FFM decreases with age while their bone mineral increases.50 The use of the 4-compartment model is generally not feasible due to the need for specialized laboratories containing the equipment that can perform all of the assays and component measurements, high cost of these methods, and time burden for participants. The 4-compartment model also estimates FM and FFM at the whole-body level and does not provide regional or specific tissue assessments. A method is considered valid when the standard error of the difference in the estimate for percent body fat is less than 3%. Errors between 3% and 4% demonstrate limited validity, and errors greater than 4% suggest that variability is too high.51,52

Reliability refers to the consistency with which something is measured. Reliability can be determined by repeating measurements on the same day or on consecutive days. Reliability coefficients are calculated as within-person coefficients of variation (CVs), where the CV is calculated as the ratio of the within-person standard deviation to the mean. Smaller CVs indicate greater reliability and ideally should be less than 2%.

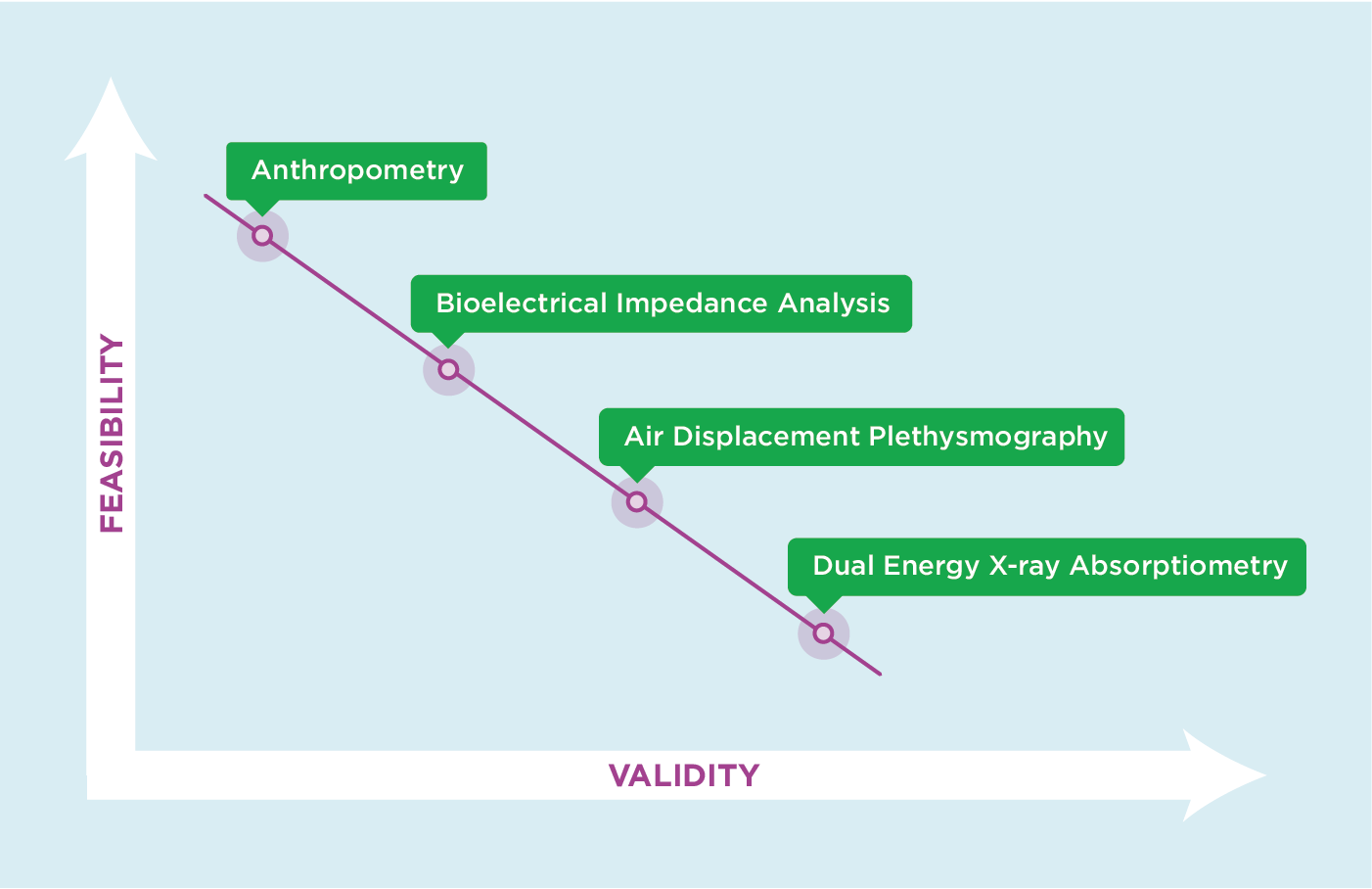

Figure 3: Feasibility/Validity Continuum of Select Adiposity Measures

The methods in this section are presented in order of most feasible and often least valid to least feasible and often most valid in population-based studies. Methods that have high validity often lack feasibility, and methods that are more feasible are frequently less valid (Figure 3).

Figure: 4: Accuracy Versus Precision

Ideally a method should have high accuracy, which is related to validity, and high precision, which is related to reliability (Figure 4), and have low cost, participant risk, and burden. In pediatric longitudinal studies, an ideal method can be used across age groups from as early as infancy to childhood and adolescence (0 to 19 years). These and other considerations are discussed in greater detail for each of the methods that follow. Although various methods can be used to assess adiposity in infants and children with disabilities, the procedures for doing so are not covered in detail within this guide.

Back to top

Methods

Each section that follows explains a method for measuring body composition and how it is conducted; provides information on the estimates of body fat and their calculation (where relevant), interpretation, and limitations; and summarizes practical issues of accessibility, training, cost, acceptability, participant burden, and risk.